From the PNB Archives: Notes on Cinderella

“In countless ways, repeated viewings of Stowell’s Cinderella bring new insights and renewed pleasures, for this is a ballet rich in inspiration, integrity, and fine detail.”

(Jeanie Thomas, Fall 1995 issue of PNB’s newsletter, Variations.)

Kent Stowell’s Cinderella premiered on May 31, 1994, and attains 32 years of age in 2026. By the end of the February 2026 series of performances, the ballet will have been performed approximately 84 times in Seattle, and 14 times on tour (in Arizona, California, and Alberta, Canada, in the 1994/1995 season). During the ballet’s first appearance, the lead roles of Cinderella and her Prince were danced by three casts: Patricia Barker and Ulrik Wivel, Louise Nadeau and Ross Yearsley, and Linnette Hitchin and Manard Stewart. In subsequent years, four to six couples have shared the roles.

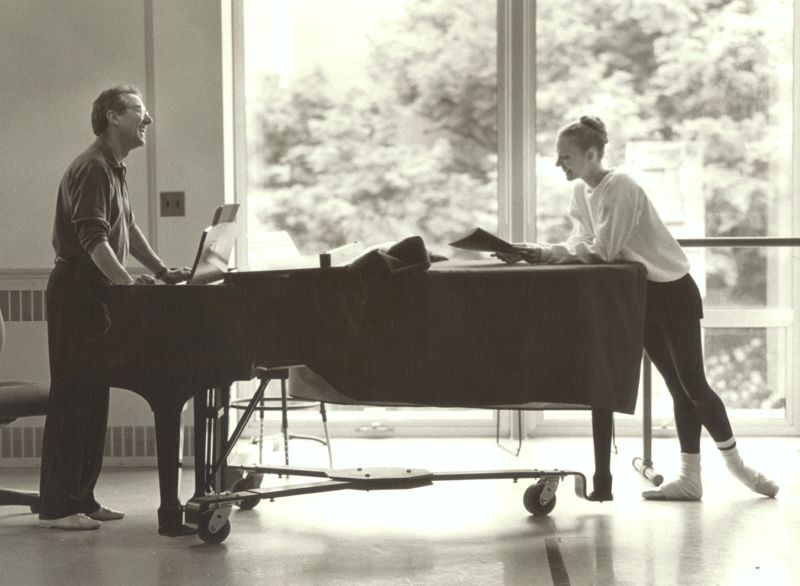

Kent Stowell and Patrica Barker during a rehearsal for Cinderella in 1994, photo © Jeffery Stanton.

This production represented another example of Stowell’s reimagining of traditional story ballets, as he had done previously in Swan Lake (Seattle premiere, 1981), the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker (1983), and The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet (1987). His Cinderella shares with some of those other works not only a reimagining of the story, but also a collaboration with notable designers, and a creative reworking of the traditional musical score (with the assistance of former PNB Orchestra conductor Stewart Kershaw.)

Cinderella was costume designer Martin Pakledinaz’s first experience working with PNB. The elegance, charm, and wit of his costumes for this ballet (based on or alluding to late 18th century fashions) led to further commissions for PNB, most notably his costume and scenic designs for PNB’s unrivaled new production of Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1997). In realizing his Cinderella costume designs, he was aided immensely by Larae Theige Hascall, PNB’s long-time Costume Shop manager [retired in 2019, after 32 years], and her crew, the number of which quadrupled in preparation for this production. 120 costumes, 25 hats, nearly three-dozen tiaras, and 30 wigs were created for Cinderella—and have been meticulously maintained by the Costume Shop over the past 30+ years.

Jodie Thomas as a Stepsister in Kent Stowell’s Cinderella, photo © Angela Sterling.

Scenic designs by Tony Straiges reflect iconic images of French art and architecture from the 16th to the 18th century. Twelve scenic drops, painted by artists employed by PNB for this production and under the direction of PNB’s chief scenic artist Edie Whitsett, allude to a Versailles vista, the Loire Valley Château de Chenonceau (forming the backdrop for Cinderella’s departure for the ball), and paintings by Antoine Watteau (in the background to the ball scene). Randall G. Chiarelli, PNB’s long-time Lighting Designer and Technical Director, described how originally Straiges wanted most of the drops printed by a computer—a process that Chiarelli notes was not only hideously expensive but produced scenic drops that were lacking in a human spirit. After Chiarelli showed Straiges an example of what Whitsett and her artists could create, Straiges was convinced, and the human scenic artists continued to paint. Chiarelli has noted that one of his favorite scenic drops in all his years at PNB is the Château de Chenonceau drop painted singlehandedly by Jan Harvey from a black and white photograph. According to Chiarelli, the consummate lighting designer, “the drop lights itself, I add nothing to it.”

PNB Company dancers in Kent Stowell’s Cinderella, photo © Angela Sterling.

This emphasis on the human element mirrors the imagination and intention of the man at the top, choreographer Kent Stowell. He wanted the ballet’s focus to be on Cinderella: on the harmonious family situation that lives in her memory (and is realized in scenes onstage); how she manages to cope with the rather dysfunctional family in which she now finds herself due to her father’s remarriage after her mother’s death; and her dream of a love relationship inspired by her memory of her parents’ happy marriage. Even the characterization of the “ugly” stepsisters is also a human one. Unlike Sir Frederick Ashton’s Royal Ballet production and others modelled on that, the stepsisters in Kent’s version are not caricatures, but are unattractive in their meanness and condescension to Cinderella and ridiculous in their affectations.

There may be a Fairy Godmother who can conjure up an amazing carriage, dancing bugs, and clock children costumed as pumpkins, but she is imaginatively humanized; she is danced by the same dancer who portrays Cinderella’s Memory Mother. The focus in this production remains on the human scale of Cinderella’s story. The final pas de deux in the ballet is not a “grand pas” in the most classic style, but a very natural and unaffected dance for our heroine and her Prince. According to Kent Stowell, the concluding pas de deux “is a picture of the very best adult love. I think it’s what we all really want. It’s what we mean by ‘happily ever after.’ ”

PNB Company dancers in Kent Stowell’s Cinderella, photo © Angela Sterling.

Whether you missed Kent Stowell’s Cinderella in the previous 30+ years and this is your first viewing, or you are renewing an acquaintance by your attendance in 2026; whether you attend just one performance, or several to see varied interpretations by different casts; it is my hope you’ll come away from the performance agreeing with the words of Jeanie Thomas cited at the beginning of this essay: “this is a ballet rich in inspiration, integrity and fine detail,” whose “repeated viewings bring new insights and renewed pleasures.”

–Sheila C. Dietrich, PNB Archivist

Footnote: Three of the artists whose work contributed so much to the beauty of this production, Edie Whitsett, Martin Pakledinaz, and Randall “Rico” Chiarelli, died in 2011, 2012, and 2024, respectively. They are remembered fondly by the PNB staff who worked with them, and especially during these performances.