By Noel Pederson

While it is one of the most famous examples in modern Western culture, Romeo and Juliet is just one of many tales of young love thwarted that have been told in many cultures across the world for thousands of years. From the Persian tale of Layla and Majnun, to the Chinese legend of The Butterfly Lovers, to Aztec mythology’s Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl – tragic stories of undying love can be found throughout human history.

In addition to building on these universal themes, Shakespeare’s play drew from several specific, existing stories from his day. The Montagues and the Capulets, or Montecchi e Cappelletti in Italian, were real families. An early reference to their dispute can be found in Dante’s Divine Comedy “Purgatorio.” These historical families were allied to feuding political parties, whose conflicts spanned all of Lombardy, rather than being confined to Verona. In the 1300s, their names would have been as synonymous with clashing families as the Hatfields and McCoys were in the 1900s.

By the 1500’s, Shakespeare’s time, Italian tales became very popular among theatre-goers. As such, it became trendy for playwrights to adapt Italian short stories for the stage. Shakespeare was almost certainly drawing from one of several Romeo and Juliet variations that were popular with readers at the time, in an effort to generate more ticket buyers. Shakespeare often used well-known Italian stories to help his plays have immediate name recognition – The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, All’s Well That Ends Well, and Measure for Measure were also popular novelle.

What set Shakespeare’s adaptation of the story apart was, of course, his unparalleled use of the English language and dramatic structure. He adeptly switches between comedy and tragedy to heighten tension, expands what were previously minor characters, adds sub-plots, and even adjusts the text’s poetic form to demonstrate character growth. For example, Romeo’s speech is intentionally overdramatic at the beginning and becomes more genuine as his love for Juliet deepens.

Romeo and Juliet went on to become one of Shakespeare’s most popular, enduring plays. In addition to being performed all over the world, thisis Shakespeare’s most-illustrated, most-filmed work, and has inspired adaptations across all genres. These include at least 24 operas, the multiple iterations of West Side Story, Duke Ellington’s 1956 jazz work “The Star-Crossed Lovers,” Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 MTV-inspired film Romeo + Juliet, and at least 14 major ballets set to Prokofiev’s classic score, one of which you are about to enjoy.

Featured photo: Galina Ulanova as Juliet and Yury Zhdanov as Romeo in Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. October 1, 1954.

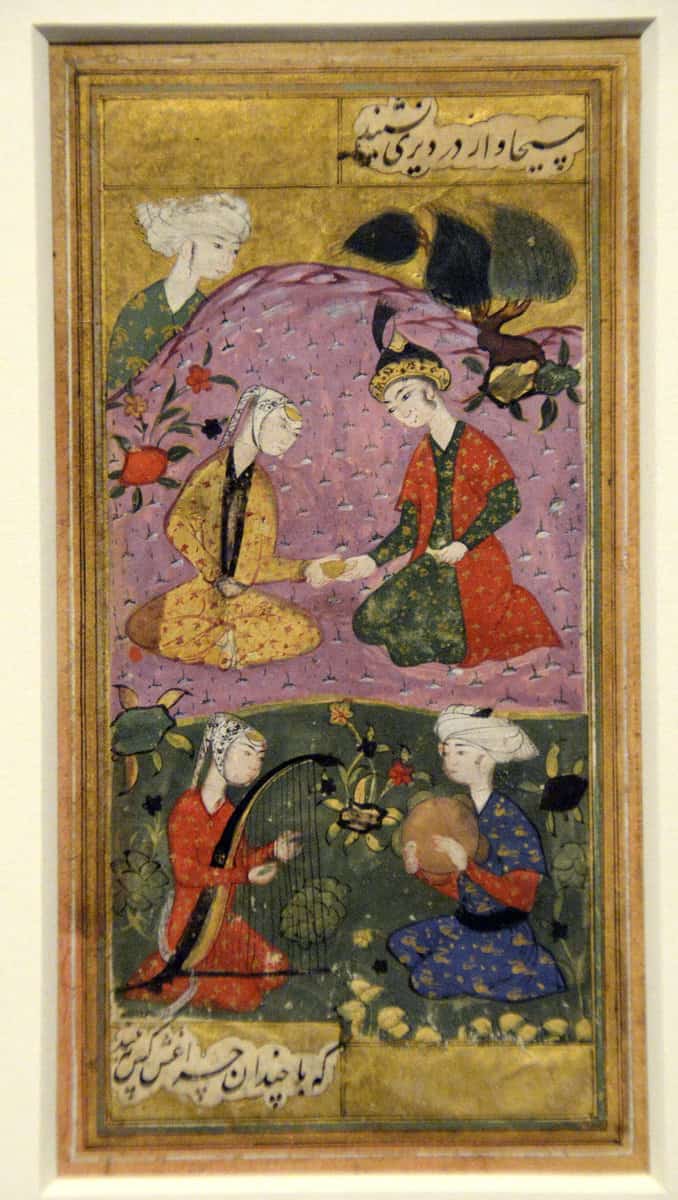

Article photos: Layla and Majnun, from Iran, 16th century CE. From the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

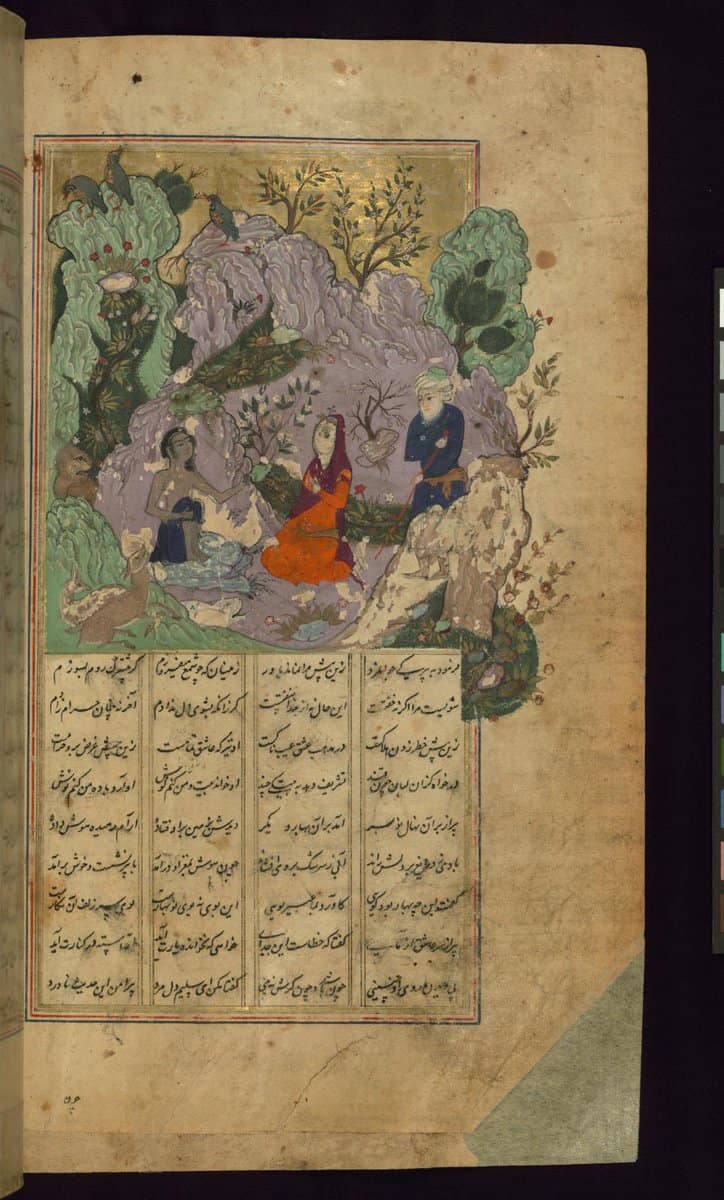

“Laylá and Majnun Meet in the Wilderness” by Nezami Ganjavi, 17th century AD, courtesy Walters Art Museum.

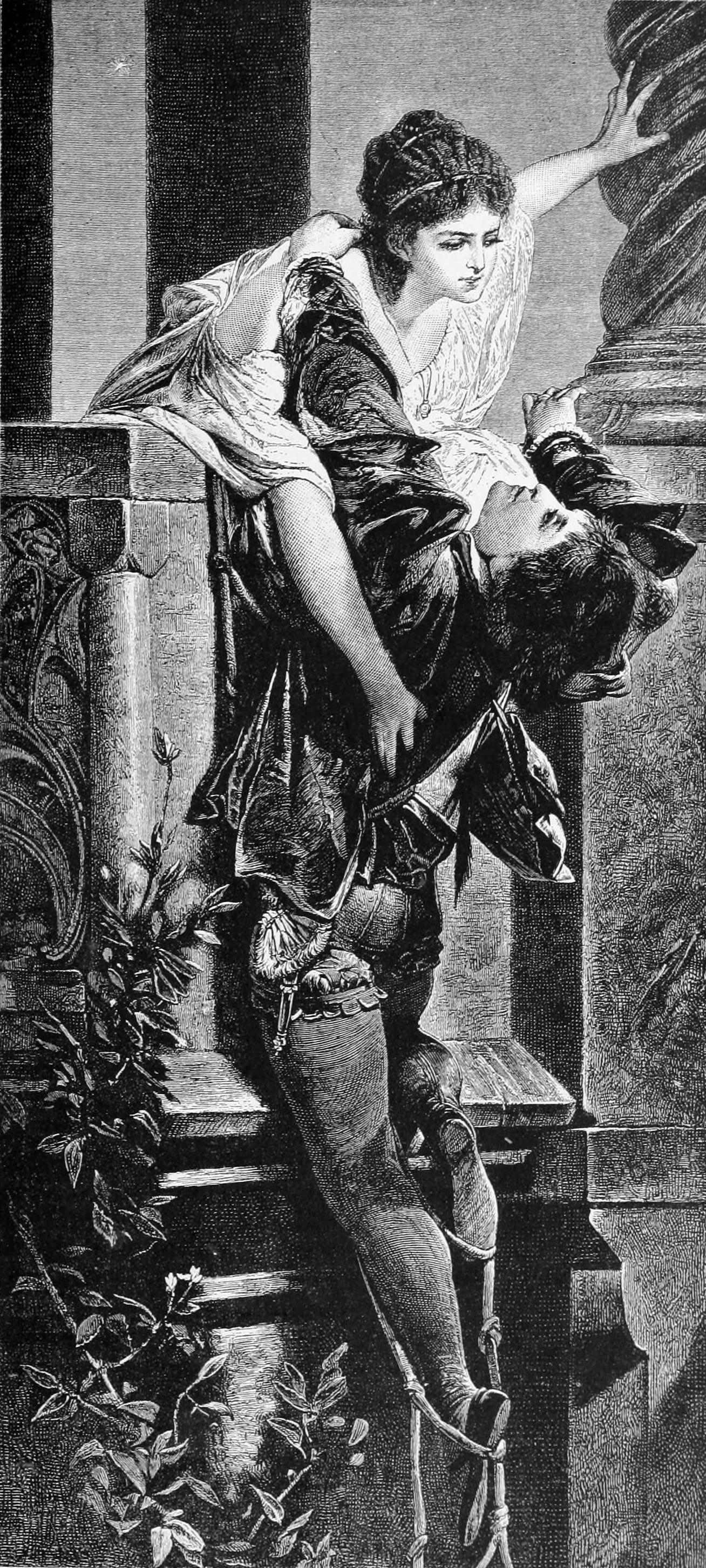

“Romeo and Juliet,” engraved from a painting by Hans Makart, 1886.

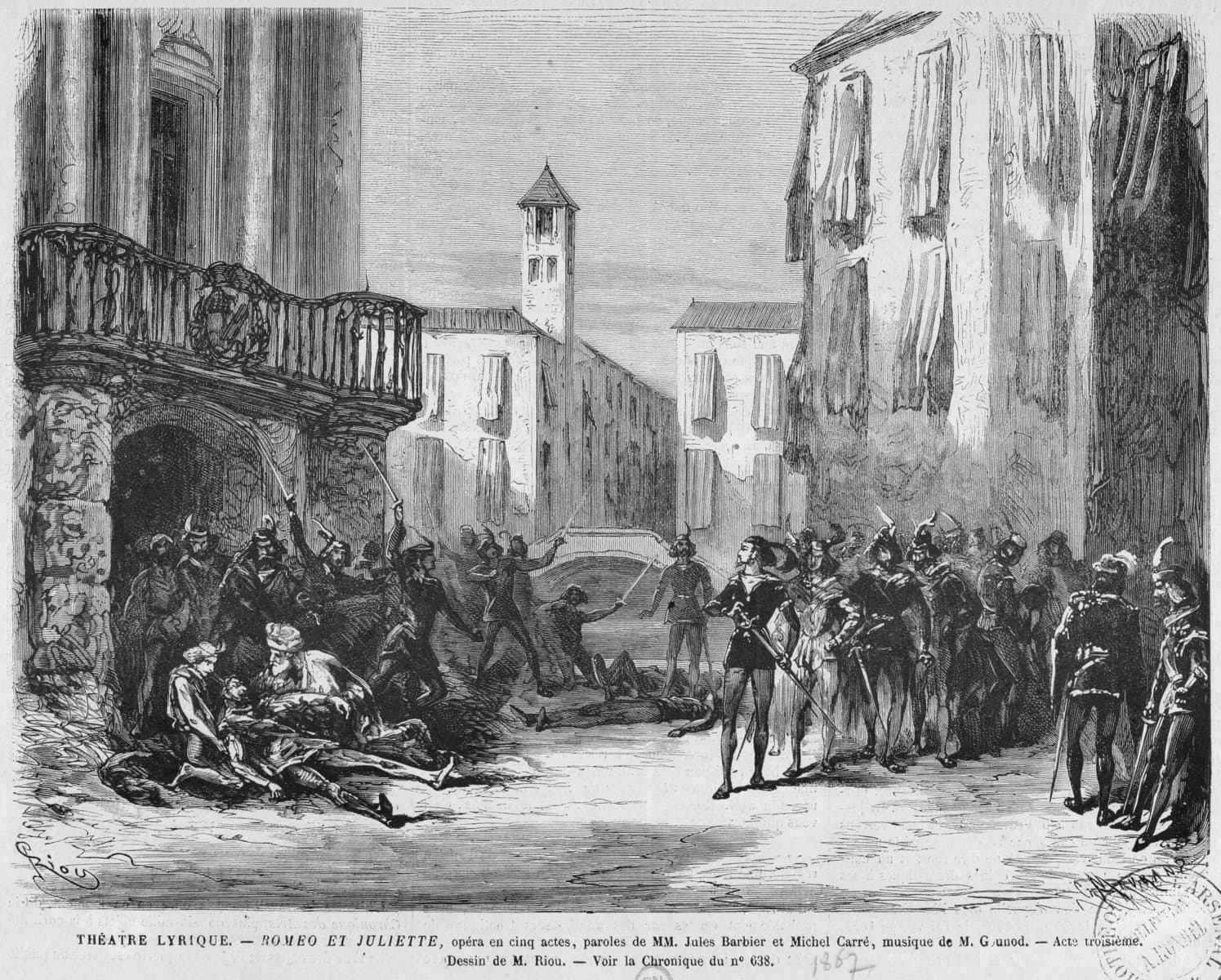

Press illustration of Act 3, scene 2, of the opera Roméo et Juliette as performed in the premiere at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris on April 24, 1867. From the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Galina Ulanova as Juliet and Yury Zhdanov as Romeo in Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. October 1, 1954. RIA Novosti archive, image #11591.

1879, United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs.

John Barrymore, Leslie Howard and Basil Rathbone in a scene from the 1936 MGM film Romeo and Juliet.

“Romeo stabs Paris at the bier of Juliet” by Henry Fuseli, circa 1809, from the Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection.

Portrait of William Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout (1622).