The Balanchine Foundation has conducted recorded interviews with dancers and stagers of Balanchine’s works like Maria Tallchief, Suzanne Farrell, Arthur Mitchell, Patricia Wilde, and more. The Balanchine Foundation’s YouTube Channel is a seemingly bottomless resource of amazing interviews. Below are just a few videos from The Balanchine Foundation about works in PNB’s current repertoire including Agon, Emeralds, The Nutcracker, and Square Dance.

Agon

A duet, Agon was specifically choreographed for Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams. Arthur Mitchell was the first Black dancer with New York City Ballet and went on to found Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969.

Interviewer Anna Kisselgoff asks Mitchell specifically about the partnering work in Agon as well as partnering with Balanchine as a choreographer.

“Experimentation rather than telling.”

Arthur Mitchell on working with Balanchine.

According to Igor Stravinsky, his starting point for Agon was a 17th-century manual of French court dances, a fact that is reflected in the headings to various sections of the score—sarabande, gaillard, bransle—and in a scattering of baroque steps and arm movements that Balanchine worked into his choreography. But, as the great critic Edwin Denby commented aptly after attending the premiere in 1957, the work “recalls court dance as much as a cubist still life recalls a pipe or guitar.”

For Agon is, in Balanchine’s own words, “the quintessential contemporary ballet.” In it, the great collaboration between himself and Stravinsky that had begun in 1928 with Apollo entered a breathtakingly new phase. Stravinsky’s music, especially the neo-classicism of his middle years, had always appealed to Balanchine, whose affinity for its rhythmic ingenuity, inspired orchestral color and flawless architecture was that of a kindred spirit. But in Agon, which Balanchine commissioned for New York City Ballet in the 1950s, Stravinsky, who was then more than seventy years old, made clear the recent and radical influence on his work of Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone, serial method. Declaring that “music like this has not been heard before,” Balanchine took up the challenge of this fiendishly—and to him, delectably—difficult score and choreographed a work that, matching the music in complexity and inventiveness, redefined ballet for our time.

Read more about Agon on The Balanchine Trust’s website & on PNB’s website.

Emeralds

In this interview Violette Verdy and Conrad Ludow, the original Emeralds couple, speak with interviewer Jennifer Dunning about the first Emeralds rehearsal, Balanchine’s love of all things French, and the freedom in Balanchine’s partnering techniques.

Watch Verdy coaching PNB dancers Margaret Mullin, Carla Körbes, and Elizabeth Murphy below.

Emeralds is a romantic evocation of France. It is also Balanchine’s comment on the French school of dancing and its rich heritage. France is the birthplace of classical ballet and French is its language. With a score by Gabriel Fauré and dancers dressed in Romantic-length tutus, Emeralds can also be a window on the nostalgia inherent in much late 19th-century art, with its idealized view of the Middle Ages, chivalry, and courtly love. Balanchine considered Emeralds “an evocation of France—the France of elegance, comfort, dress and perfume.”

Read more about the full Jewels ballet from The Balanchine Trust & the history of the ballet on our blog.

The Nutcracker

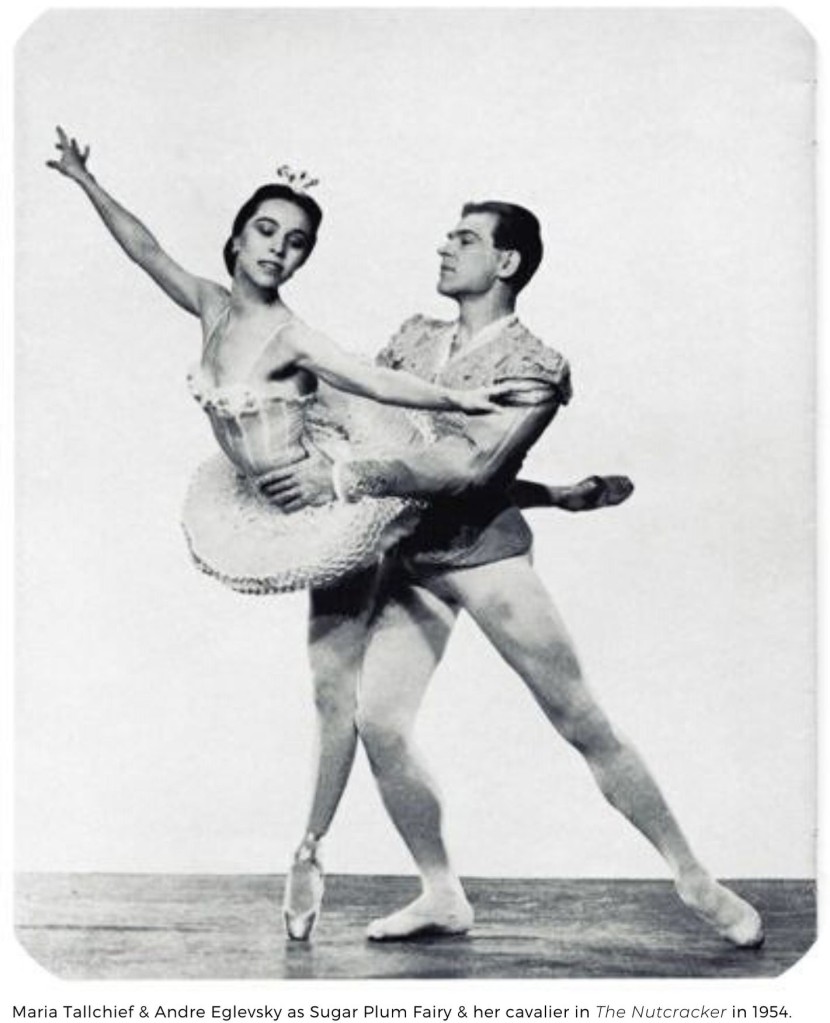

Watch an excerpt of an interview with Maria Tallchief, New York City Ballet’s first prima ballerina, and the first Native American principal dancer, and originator of many Balanchine roles including Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker.

When George Balanchine staged The Nutcracker for New York City Ballet in 1954, it was the six-year-old company’s most ambitious project to date. The choreographer spent more than half of the production’s $40,000 budget on the Christmas tree, infuriating Morton Baum, chair of New York City Center’s finance committee, which had put up the money. Baum asked, “George, can’t you do it without the tree?” to which Balanchine replied, “The ballet is the tree.”

Balanchine had danced in the Maryinsky Theater’s production in St. Petersburg as a child. His roles included soldier, mouse king, little prince, and the lead in the hoop dance, which had been choreographed by its original interpreter, Alexander Shiryaev, for the 1892 premiere. Balanchine remembered the luxurious days before the Russian revolution and held them as an ideal. When Baum asked him to stage The Nutcracker, banking on the popularity of The Nutcracker Suite in the United States, Balanchine said, “If I do anything, it will be full-length and expensive.”

Read more about George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker HERE & HERE.

Square Dance

Balanchine’s Square Dance combines classical ballet, 17th-century court dance, and American country dancing. In the original 1957 production, the musicians were on stage and a square dance caller was brought in to call out the steps. Balanchine revived Square Dance in 1976, dispensing with the caller, putting the orchestra in the pit, and adding a celebrated solo for the principal male dancer.

Watch dancer Patricia Wilde speak specifically about dancing with Balanchine, and watch her dance the principal role in the original version of Square Dance (with the square dance caller) below.

Writing about Square Dance, Balanchine explained, “Ballet and other forms of dance of course can be traced back to folk dance. I have always liked watching American folk dances, especially in my trips to the West, and it occurred to me that it would be possible to combine these two different types of dance, the folk and the classic, in one work. To show how close the two really are, we chose old music also based on ancient dances. The spirit and nerve required for superb dancing are close to what we always want in ballet performances, which is one way perhaps of explaining why so many American dancers are so gifted. The invention, its superb preparation for risks, and its high spirits are some of the things I was trying to show in this ballet.”

Read more about Square Dance on The Balanchine Trust’s website & on PNB’s repertory page.